Wuhan is the capital city of Hubei Province in the central area of China. It has been famous for its economy based on state-owned enterprises, such as Wuhan Iron and Steel Company. In recent years, it has significantly developed the high-tech industry and promoted the development of mega-urban projects and new towns. Wuhan is also meaningful to observe city recovery from Covid and governance innovations, such as the ‘co-production’ initiative.

Urban Level

At the urban level, we use Wuhan as a case to investigate two ongoing new-town initiatives for urban development and rethink China’s urban governance.

Two New Towns

Wuhan is currently undertaking two new-town development agendas: Changjiang New Area and Wuhan New Town. Both were proposed by the main leaders of Hubei Province.

In 2017, the top leader of Hubei Province then put forward a plan to build Changjiang New Area alongside the Yangtze River. Similar to the plan of Xiong-An New Area, the plan of Changjiang New Area also depicted the starting area, mid-term development area and long-term development area. The starting area covers 30 square kilometres. It planned to apply for the endorsement of National New Areas. However, the central state ceased approving any new national new areas after Xiong-An. Changjiang New Area was suspended until 2020 when the provincial government endorsed it to become a provincial-level new zone, allowing the development of Changjiang New Area to resume.

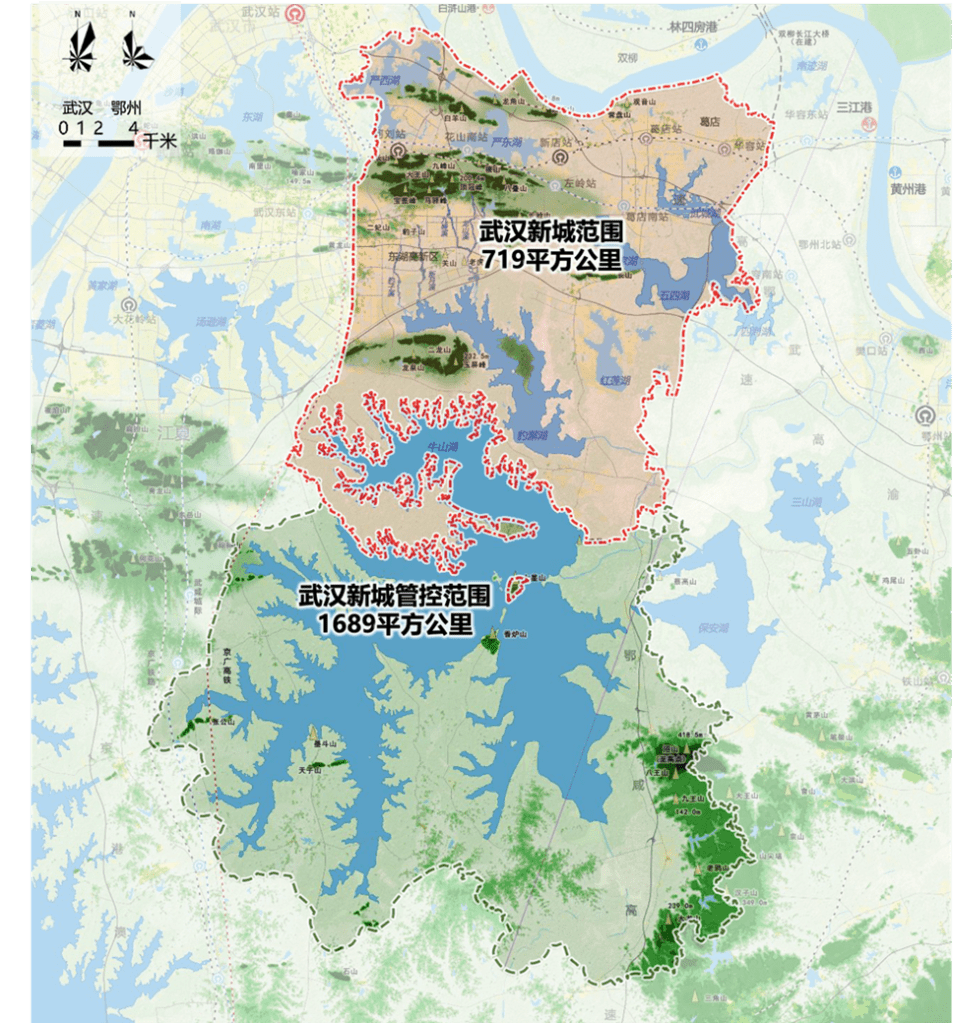

Wuhan New Town aims to solve inter-city competition by initiating a new development area. The provincial government recognizes the uneven development of cities in Hubei province and urges Wuhan to take the lead, stimulating and cooperating with cities surrounding Wuhan. Therefore, Wuhan New Town is located on the east edge of Wuhan next to Ezhou city.

Challenges

While new town development has been a typical tactic for urban growth, Wuhan faces two significant challenges. First, the development agendas are proposed and driven by different leaders of the provincial government during their term times. Once their terms end, whether the mega-urban project will continue is uncertain. Second, two large-scale urban development initiatives are being undertaken at the same time, requiring substantial resources and funding.

Neighbourhood level

In Wuhan, we also focus on governance changes at the neighbourhood scale, represented by the “co-production” (gongtong dizao) initiative. Initiated by the Hubei provincial government, the ‘co-production’ initiative focuses on organising ‘small and practical works around people’s homes’. Throughout this process, it adheres to principles of party leadership and citizen participation, promoting joint decision-making, collaborative development, shared management, collective evaluation, and shared outcomes. By co-producing a better living environment, the initiative aims to enhance people’s overall sense of contentment, happiness, and security. Taking Huajin Neighbourhood as an example, we observe how local state agencies translate this initiative into practice, promoting community regeneration while producing new forms of local governance networks.

Co-production as governance innovation

Huajin is a mixed neighbourhood in Wuchang District. Built in 1999, the neighbourhood has gradually deteriorated, with residential buildings often suffering from issues such as water leaks. The recent round of ‘co-production’ in Huajin started in 2023, aiming to ‘co-produce’ the renovation plans with residents through various participatory planning activities (see Figure 3 for an example). Wuhan University (WHU) was invited to organise these activities, seeking to guide residents in identifying neighbourhood issues and reaching a consensus on renovation plans.

Apart from physical changes to the neighbourhood, ‘co-production’ also aims to achieve, as one member of the WHU team highlights, ‘re-vitalising grassroots organisational system and enhancing neighbourhood social capital’. Such organisational tasks go beyond the scope of community renovation and involve community party-building as a key driving force. Huajin has made some explorations in this area, such as cultivating teams of community planners, community volunteers and sent-down party members (Figure 4).

Co-production for community regeneration

While nominally focused on “small and practical matters around homes,” the renovation of old and dilapidated neighbourhoods is often carried out by professional construction companies and typically requires investments in the tens of millions. In the case of Huajin, the regeneration was financially supported and implemented by a state-owned construction company who views the regeneration as an investment opportunity. Tensions emerged during the implementation stage. The traditional model of old neighbourhood renovation—although it may include elements of public participation—did not always align with co-production and community mobilization advocated by the ‘co-production’ initiative. One solution to coordinate such tensions was through the powerful role of the local party-state. On one hand, the grassroots party-state played a crucial role in social mobilization; on the other hand, the local state employs ‘planning’ as a tool to promote ‘integral design and integral construction.’ In such a mode, community regeneration, which emphasizes social value and has a relatively low return-on-investment, is packaged with other development projects that have relatively higher expected returns. However, the effectiveness of this mode remains to be seen in the long term.